Deploying new tools to stem loss of bats

Tucked away in the darkness of caves, mineshafts and underpasses across America, an insidious killer continues to decimate one of North America’s most fascinating, economically valuable and underappreciated wild animals: bats.

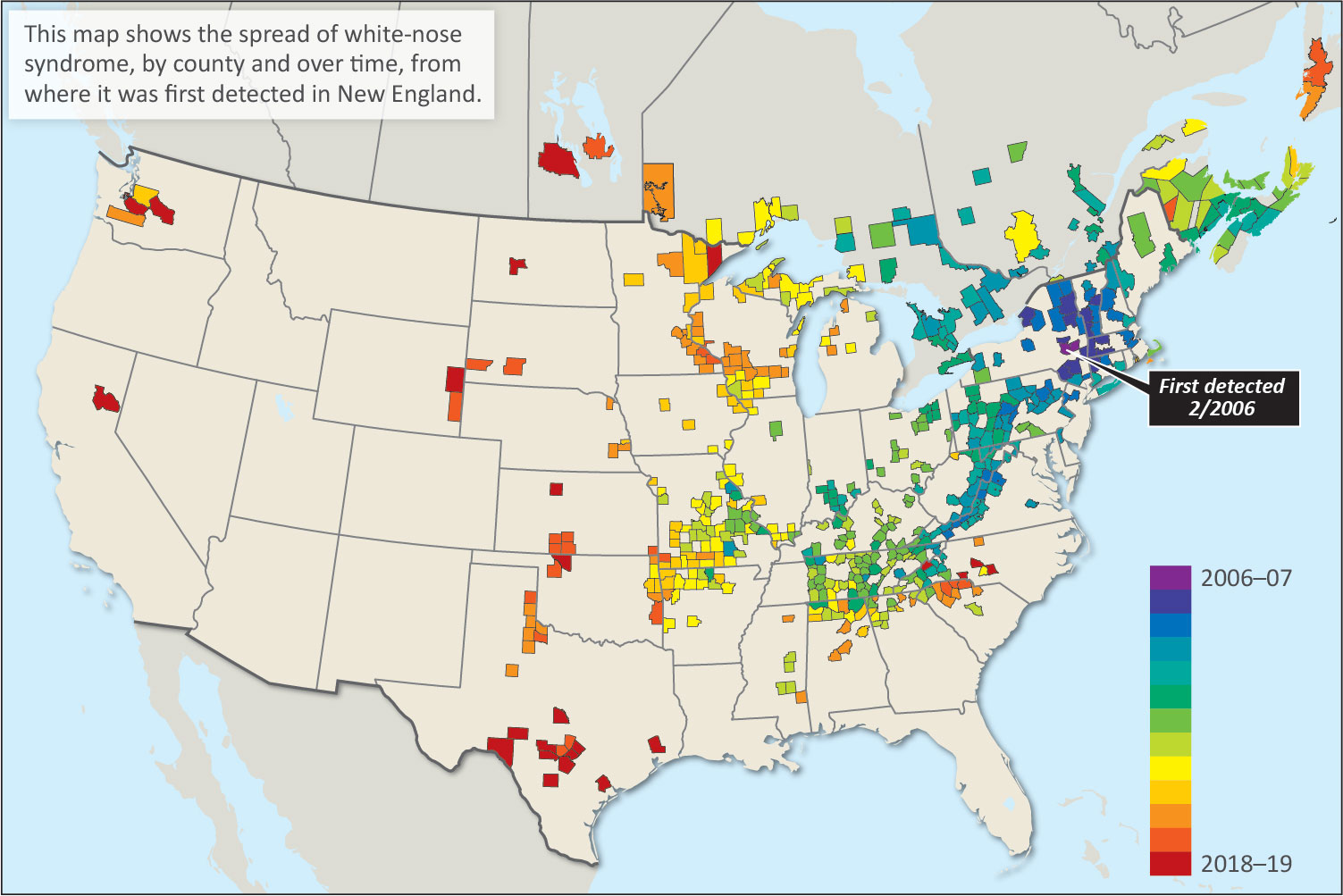

White-nose syndrome, a disease caused by the fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans, ranks as one of the most urgent threats to wildlife in the United States. After its first detection in 2007 near Albany, New York, the fungus has quickly spread throughout the Appalachian region to Midwestern states, Canada, and, more recently, to Texas, South Dakota, California and Washington.

The fungus lurks and lingers in damp, dark places, attacking bats while they hibernate through the winter. The white, fuzzy fungus often covers a bat’s face – hence the name – and causes them to behave erratically, burning energy they need to survive the winter.

Scientists estimate the disease has killed more than 6 million bats across the United States, with more dying every year.

“The losses are tremendous,” said Dr. Winifred Frick, chief scientist at Bat Conservation International. “This crisis isn’t academic – these animals play a vital ecological role and contribute nearly $4 billion worth of free insect control to U.S. agricultural efforts.

“White-nose disease represents a dire threat, not just in terms of wildlife conservation, but also for the country as a whole. We need to move quickly to halt the spread of the disease and turn things around for these amazing creatures.”

Working with a variety of public and private partners in 2017, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and NFWF created the Bats for the Future Fund to test and deploy advanced techniques and tools to address this urgent conservation need.

During the fund’s most recent round of grant-making, completed in late 2018, the fund awarded more than $1.1 million to combat white-nose syndrome. These awards leveraged more than $900,000 in match from grantees, generating a total conservation impact of $2 million.

Grant awards included nearly $112,000 to Bat Conservation International. Researchers with the organization will test the effectiveness of two nontoxic agents, ultraviolet light and polyethylene glycol, in treating mine walls at the northern and southern edge of the disease’s advance.

Other grants supported through the fund will advance similarly cutting-edge techniques. One project will test automatic spray technology to apply liquid or gel treatment to bats as they fly into or out of roosts, then measure biomarkers to assess success rates. Another project will explore a gene silencing system, induced by a virus, to undermine the fungus causing white-nose syndrome. Yet another will assess the use of antifungal fumigants to treat bat hibernacula.

“White-nose syndrome poses a significant threat to bats in North America,” said Dr. Jeremy Coleman, national white-nose syndrome coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “If we can’t improve survival of susceptible species, we could see the extinction of some native bats.

“NFWF is playing a significant role by creating partnerships that leverage federal dollars to raise private funds to help support crucial frontline efforts. With time running short for some species, we need to do all we can right now to reduce the damage from white-nose syndrome and conserve our native bats.”

This story originally appeared in NFWF's 2019 Annual Report.